Photo: Meiyer Torrisi, Pueblo Zoo

-

Natural History

-

SSP

-

Organizations

-

Conservation Action

<

>

|

Conservation Status

IUCN: Near Threatened European Threat Status is Rare CITES: |

Introduction:

|

Physical Characteristics

The Cinereous Vulture is believed to be the largest bird of prey in the world, together with the Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus) males (Houston et al. 2017, Meyburg et al. 2017). Females are slightly larger than males. This huge bird measures 98–120 cm (3 ft. 3 in–3 ft. 11 in) long with a 2.5–3.1 m (8 ft. 2 in–10 ft. 2 in) wingspan. Males can weigh from 6.3 to 11.5 kg (14 to 25 lb), whereas females can weigh from 7.5 to 14 kg (17 to 31 lb). It is thus one of the world's heaviest flying birds. Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 73–89 cm (29–35 in), the tail is 33–41 cm (13–16 in) and the tarsus is 12–14.6 cm (4.7–5.7 in) (Brown and Amadon 1986, Ferguson-Lee and Christie 2001).

It is a dark brown bird, has broad wings which have a serrated appearance to their trailing edges, owing to the pointed tips of the secondary feathers (Clark 1999). In flight, the tips of the wings show seven deeply splayed ‘fingers’, and this species has a short, slightly wedge-shaped tail (Del Hoyo et al. 1994). The bare skin on the head and neck is blue-grey, and there is some darkly-coloured down on the head (Del Hoyo et al. 1994) and a brown ‘Elizabethan’ ruff of feathers around the hind neck (Clark 1999). This ruff is paler in older individuals (Del Hoyo et al. 1994) giving the Cinereous Vulture its alternative name of ‘monk vulture’, as it is thought to resemble a monk’s hood. It has a very powerful bill, which is mostly dark but has a lighter area at the base. The legs and feet of this species are pale in colour (Clark 1999).

Juvenile Cinereous Vultures are darker than adults and often look almost black. They also lack the pale line on the underside of the wing, and have pinkish to pale grey skin on the head (Del Hoyo et al. 1994, Clark 1999). As the juvenile Cinereous Vulture approaches maturity, the down on its head gets paler and its eyes change from dark brown to a reddish-brown (Clark 1999).

The Cinereous Vulture is believed to be the largest bird of prey in the world, together with the Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus) males (Houston et al. 2017, Meyburg et al. 2017). Females are slightly larger than males. This huge bird measures 98–120 cm (3 ft. 3 in–3 ft. 11 in) long with a 2.5–3.1 m (8 ft. 2 in–10 ft. 2 in) wingspan. Males can weigh from 6.3 to 11.5 kg (14 to 25 lb), whereas females can weigh from 7.5 to 14 kg (17 to 31 lb). It is thus one of the world's heaviest flying birds. Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 73–89 cm (29–35 in), the tail is 33–41 cm (13–16 in) and the tarsus is 12–14.6 cm (4.7–5.7 in) (Brown and Amadon 1986, Ferguson-Lee and Christie 2001).

It is a dark brown bird, has broad wings which have a serrated appearance to their trailing edges, owing to the pointed tips of the secondary feathers (Clark 1999). In flight, the tips of the wings show seven deeply splayed ‘fingers’, and this species has a short, slightly wedge-shaped tail (Del Hoyo et al. 1994). The bare skin on the head and neck is blue-grey, and there is some darkly-coloured down on the head (Del Hoyo et al. 1994) and a brown ‘Elizabethan’ ruff of feathers around the hind neck (Clark 1999). This ruff is paler in older individuals (Del Hoyo et al. 1994) giving the Cinereous Vulture its alternative name of ‘monk vulture’, as it is thought to resemble a monk’s hood. It has a very powerful bill, which is mostly dark but has a lighter area at the base. The legs and feet of this species are pale in colour (Clark 1999).

Juvenile Cinereous Vultures are darker than adults and often look almost black. They also lack the pale line on the underside of the wing, and have pinkish to pale grey skin on the head (Del Hoyo et al. 1994, Clark 1999). As the juvenile Cinereous Vulture approaches maturity, the down on its head gets paler and its eyes change from dark brown to a reddish-brown (Clark 1999).

|

Habitat and Range

|

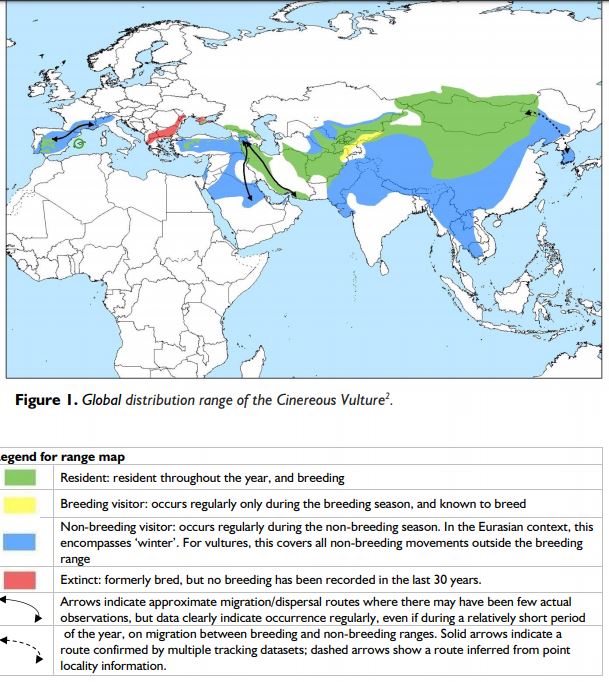

The species is a partial migrant (Bildstein 2006). Sedentary in some areas, but many individuals winter south of the breeding range, and there is a considerable degree of nomadism. The global range covers 64 countries, of which 19 are supporting breeding populations, whilst in a further 41 countries it is recorded as vagrant or wintering . The species is extinct in 15 countries

Feeding & Behavior

Like all the Old World vultures (except the Palm-nut Vulture Gypohierax angolensis (Carneiro 2017)), the Cinereous Vulture feeds mostly on carrion. Its diet consists mainly of carrion from medium-sized or large mammal carcasses, although snakes and insects have also been recorded as food items. Live prey is rarely taken (Batbayar et al. 2006). It mainly feeds on the carcasses of rabbits, sheep and wild ungulates (Hiraldo 1976, Corbacho et al. 2007, Yamac and Günyel 2010). However, changes in the availability of prey over the last 30 years have led to a decrease in the number of rabbits in its diet and an increase in the consumption of domestic ungulates (Corbacho et al. 2007, Costillo et al. 2007, Moreno-Opo et al. 2010).

It spends much time soaring overhead in search of food, over a variety of habitats including treeline, agricultural habitats with patches of forests, bare mountains, steppe and open grasslands. It is a central place forager around the breeding colonies (Carrete and Donázar 2005) being more common in areas with a higher prey abundance, especially extensive livestock, wild ungulates and lagomorphs (Costillo et al. 2007).

Like all the Old World vultures (except the Palm-nut Vulture Gypohierax angolensis (Carneiro 2017)), the Cinereous Vulture feeds mostly on carrion. Its diet consists mainly of carrion from medium-sized or large mammal carcasses, although snakes and insects have also been recorded as food items. Live prey is rarely taken (Batbayar et al. 2006). It mainly feeds on the carcasses of rabbits, sheep and wild ungulates (Hiraldo 1976, Corbacho et al. 2007, Yamac and Günyel 2010). However, changes in the availability of prey over the last 30 years have led to a decrease in the number of rabbits in its diet and an increase in the consumption of domestic ungulates (Corbacho et al. 2007, Costillo et al. 2007, Moreno-Opo et al. 2010).

It spends much time soaring overhead in search of food, over a variety of habitats including treeline, agricultural habitats with patches of forests, bare mountains, steppe and open grasslands. It is a central place forager around the breeding colonies (Carrete and Donázar 2005) being more common in areas with a higher prey abundance, especially extensive livestock, wild ungulates and lagomorphs (Costillo et al. 2007).

Breeding

Nests are normally built on trees, sometimes on cliffs or even on the ground (Mebs and Schmidt 2006).

The Cinereous Vulture has the longest breeding period of all raptors in Europe. The incubation period of the single egg averages 57 days (range 50-68 days). The young spend 110-120 days in the nest (with extreme ranges from 88-137 days) (Moreno-Opo 2007a). After fledging the young return to the nest for a while to obtain food from the adults and to roost at night (Mebs and Schmidt 2006). Breeding parameters of the species are not well known for the entire breeding range.

Nests are normally built on trees, sometimes on cliffs or even on the ground (Mebs and Schmidt 2006).

The Cinereous Vulture has the longest breeding period of all raptors in Europe. The incubation period of the single egg averages 57 days (range 50-68 days). The young spend 110-120 days in the nest (with extreme ranges from 88-137 days) (Moreno-Opo 2007a). After fledging the young return to the nest for a while to obtain food from the adults and to roost at night (Mebs and Schmidt 2006). Breeding parameters of the species are not well known for the entire breeding range.

Conservation Issues

- It is very important to highlight the main strongholds of the Cinereous Vulture population: Mongolia holds approximately 50% of the species’ global population, and Spain more than 20% (representing 90% of the European population). These facts must be kept in mind when identifying global threats to the species and when developing conservation actions.

- As for most, if not all, vulture species, poisoning is the most severe threat to the Cinereous Vulture. This is the reason for the species’ extinction in significant part of its original range, the cause of declines in more than half of its current range and one of the main constraints for its recovery. In general, poison is not used to intentionally kill vultures – these birds are normally secondary or tertiary victims of poison used against predators (foxes, wolves, feral dogs, etc.) regarded to be in conflict with human activities such as livestock husbandry and hunting. Poisoning can also be unintentionally caused by agrochemicals (pesticides), veterinary pharmaceuticals (used in livestock), and lead ammunition from hunting activities. Poisoning is not the only threat affecting the Cinereous Vulture: electrocution and collision with electricity infrastructure are also causing direct mortality across its entire range. At present, the persecution or deliberate killing of birds is considered a threat in Central Asia, rather than Europe.

- The species is also threatened by factors that affect breeding success and distribution. The decline of herbivores (wildlife and livestock), resulting in a reduction of animal carcasses in the wild, is considered to have a negative impact on the species. Disturbance caused by human activities during the breeding season (which is protracted for this species, see section 2.6) can also have a negative effect on breeding success.

References

Content taken from the Flyway Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cinereous Vulture. See this document for full bibliography.

Content taken from the Flyway Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cinereous Vulture. See this document for full bibliography.

|

Date of Last PVA/B&T Plan

12/30/13 Current Population Size (N) 24.30.0 (54) Current Number of Participating AZA Member Institutions 21 member & 4 nonmember Projected % GD at 100 years or 10 generations** 79% |

|

2016 Studbook

Eurasian Black Vulture (Aegypius monachus) AZA Species Survival Plan® Yellow Program |

Population Analysis & Breeding and Transfer Plan

Eurasian Black Vulture (Aegypius monachus) AZA Species Survival Plan® Yellow Program |

Sustainability Report

Eurasian Black Vulture

(Aegypius monachus)

AZA Species Survival Plan® Yellow Program

Eurasian Black Vulture

(Aegypius monachus)

AZA Species Survival Plan® Yellow Program

Officers

|

Name

|

Organization

|

Position

|

|

Denver Zoo

|

SSP Program Leader & Studbook

|

|

Brandywine Zoo

|

Studbook Program Leader

|

AZA SAFEThe African Vulture SAFE program is focusing on the conservation, restoration, and field research of the African vultures.

|

VulProVulPro’s work in South Africa involves instrumental veterinary toxicological research, colony monitoring, and rehabilitation of injured vultures. Additionally, VulPro breeds nonreleasable Cape Vultures, African White-backed Vultures, Lappet-faced Vultures, and White-headed Vultures as part of a conservation breeding and reintroduction program where all offspring are returned to the wild. Public education is also a large aspect of VulPro’s work, both to school groups and local communities as well as visiting researchers looking to gain invaluable field experience in areas such as capturing, tagging, monitoring and rescuing vultures.

VulPro is one of the organizations supported by African Vulture SAFE. |

AZA SAFEThe African Vulture SAFE program is focusing on the conservation, restoration, and field research of the African White-Backed vulture.

|

Flyway Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cinereous VultureThis Flyway Action Plan aims to integrate the European action framework, including implementation best practice experience, into the global picture and to propose a coordinated and coherent framework for conservation of the Cinereous Vulture in its entire distribution range.

|