-

Natural History

-

SSP

-

Organizations

<

>

|

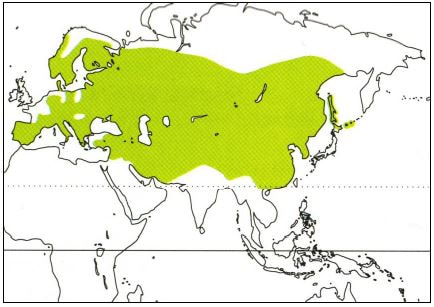

Taxonomy & Range

The Eurasian Eagle Owl (also known as the Great, or Northern Eagle Owl) was first described scientifically by Linnaeus in 1758, based on a Swedish type specimen. The species has a significant range which includes most of Europe and Scandinavia, western Asia, and eastern Asia (north of the Himalayas). The Eurasian Eagle Owl forms a superspecies with Great Horned Owl (B. virginianus), as well as Rock (B. bengalensis), Pharaoh (B. ascalaphus), and Cape Eagle Owls (B. capensis). Geographical boundaries between these species are not clear, as there appear to be intergrading populations, as well as significant individual morphological variations. Overall, 14 subspecies of Eurasian Eagle Owl are recognized (Holt et al., 1999). |

General Ecology

Weighing between 1.5 and 4.2 Kg, with a wingspan of up to 1.88 m, the Eurasian Eagle Owl is among the world’s largest owls. These owls inhabit woodland, open forest, taiga, and steppe. It has been suggested that both habitat selection and nesting success rates depend primarily on the availability of specific suitable prey species, such as European Rabbits, Oryctolagus sp. (Martinez et al., 2003; Penteriani et al., 2002). Highly adaptable, eagle owls may be active either at night or in the day, hunting a variety of prey from the air or an open perch. The majority of the diet consists of small mammals, but may include larger mammals, birds up to the size of herons (Ardea) or buzzards (Buteo), and reptiles.

Weighing between 1.5 and 4.2 Kg, with a wingspan of up to 1.88 m, the Eurasian Eagle Owl is among the world’s largest owls. These owls inhabit woodland, open forest, taiga, and steppe. It has been suggested that both habitat selection and nesting success rates depend primarily on the availability of specific suitable prey species, such as European Rabbits, Oryctolagus sp. (Martinez et al., 2003; Penteriani et al., 2002). Highly adaptable, eagle owls may be active either at night or in the day, hunting a variety of prey from the air or an open perch. The majority of the diet consists of small mammals, but may include larger mammals, birds up to the size of herons (Ardea) or buzzards (Buteo), and reptiles.

|

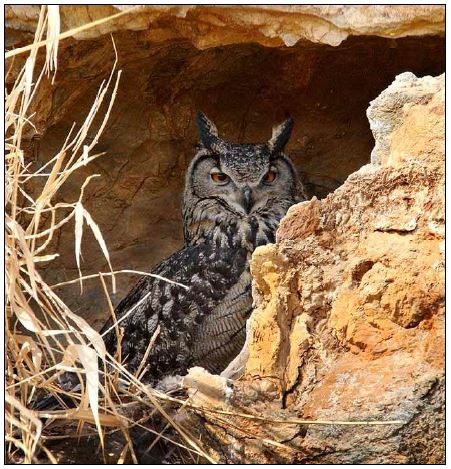

Breeding Biology

Breeding as early as two years of age, these owls tend to be monogamous, using the same nesting site year after year; eagle owls have been known to nest on cliffs, in nests built by other birds, or on the ground. As many as four eggs (but more often two) are laid, with a three-day laying interval, and incubated (almost exclusively by the female) for 34-36 days. Adult owls tend to be very sensitive, abandoning eggs and even young at the slightest disturbance. White and fluffy at hatch, owlets develop quickly, feeding themselves at the nest after only three weeks. Remarkable increases in mass are noted in the first 30 days, and between days 40-45. After the age of 80-90 days, chicks (still fed by their parents) move widely, ranging up to 1500 m from the nest in one study. By seven weeks, young are able to fly; the owlets are independent at 150-160 days’ of age (Penteriani et al., 2004). Cainism is common in this species, with older young preying upon younger owlets. |

Present Status & Threats to Survival

The Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) is not currently threatened with extinction, with an estimated global range of over 10 million square kilometers (IUCN, 2017); the wild European population may number 25,000 pairs (Holt et al., 1999). There have, however, been marked declines in local populations, as well as regional extinctions. Overall population density is low (as is the case for many large raptors); hence habitat loss has taken a significant toll on the species. Additionally, poisoning (via agricultural applications) and deaths through road traffic and barbed wire may be significant (Holt et al., 1999). Eagle owls are subject to relatively high levels of commercial pressure, and are coveted by hobbyists; they have been listed on CITES Appendix II since April 1977 (CITES, 2017). Legal protection in many parts of Europe has helped some populations to recover, as have reintroduction programs (including those in Germany, France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Scandinavia); challenges faced by reintroduction programs include high mortality and low reproductive success (Holt et al., 1999).

The Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) is not currently threatened with extinction, with an estimated global range of over 10 million square kilometers (IUCN, 2017); the wild European population may number 25,000 pairs (Holt et al., 1999). There have, however, been marked declines in local populations, as well as regional extinctions. Overall population density is low (as is the case for many large raptors); hence habitat loss has taken a significant toll on the species. Additionally, poisoning (via agricultural applications) and deaths through road traffic and barbed wire may be significant (Holt et al., 1999). Eagle owls are subject to relatively high levels of commercial pressure, and are coveted by hobbyists; they have been listed on CITES Appendix II since April 1977 (CITES, 2017). Legal protection in many parts of Europe has helped some populations to recover, as have reintroduction programs (including those in Germany, France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Scandinavia); challenges faced by reintroduction programs include high mortality and low reproductive success (Holt et al., 1999).

Conservation Priorities

Conservation measures that have been undertaken include 1legal protection in many parts of the species’ range, 2international agreements to protect the species from commercial trade (i.e. CITES), and 3extensive research on the breeding habits and ecology of European populations. Despite protected status, the species is still persecuted in many parts of their range (Holt et al., 1999), pesticides may be particularly problematic to these apex predators, no detailed data on Asian populations exist, and efforts must be made to protect nesting territories (and potential territories) from additional development. Moving forward, lessons learned from Eurasian Eagle Owl conservation and reintroduction programs may be crucial to the success of efforts to conserve critically endangered relatives (including Blakiston’s eagle owl, Bubo blakistoni, among the world’s rarest owls).

Conservation measures that have been undertaken include 1legal protection in many parts of the species’ range, 2international agreements to protect the species from commercial trade (i.e. CITES), and 3extensive research on the breeding habits and ecology of European populations. Despite protected status, the species is still persecuted in many parts of their range (Holt et al., 1999), pesticides may be particularly problematic to these apex predators, no detailed data on Asian populations exist, and efforts must be made to protect nesting territories (and potential territories) from additional development. Moving forward, lessons learned from Eurasian Eagle Owl conservation and reintroduction programs may be crucial to the success of efforts to conserve critically endangered relatives (including Blakiston’s eagle owl, Bubo blakistoni, among the world’s rarest owls).

Notes on Eagle Owls in Captivity

The first recorded appearance of Eurasian Eagle Owls in North American zoological collections occurred in December 1959, with the importation of 01.00.01 Danish birds to the San Diego Zoo. The first successful North American captive hatch occurred at Calgary Zoo in July 1970. While various subspecies (including Bubo bubo bubo, B. b. turcomanus, B. b. hispanus) have been maintained historically, AZA’s Raptor TAG manages the species only at the specific level.

The first recorded appearance of Eurasian Eagle Owls in North American zoological collections occurred in December 1959, with the importation of 01.00.01 Danish birds to the San Diego Zoo. The first successful North American captive hatch occurred at Calgary Zoo in July 1970. While various subspecies (including Bubo bubo bubo, B. b. turcomanus, B. b. hispanus) have been maintained historically, AZA’s Raptor TAG manages the species only at the specific level.

Sources Cited:

1. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (2016). www.cites.org. Available 7/2017.

2. Holt, D.W., Berkley, R., Deppe, C., Enriquez Rocha, P.L., Petersen, J.L., Rangel Salazar, J.L., Segars, K.P., & K.L. Wood. (1999). Family Strigidae (Typical Owls). Pp. 76-243 in: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1999). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barnowls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

3. International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2016). www.iucnredlist.org. Available 7/2017.

4. Martinez, J.A., Serrano, D., & Zuberogoitia, I. 2003. Predictive models of habitat preferences for the Eurasian eagle owl Bubo bubo: a multiscale approach. Ecography 26:21-28.

5. Penteriani, V., Delgado, M. M., Maggio, C., Aradis, A., & Sergio, F. 2004. Development of chicks and predispersal behavior of youn in the Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo). Ibis 147 (1):155-168.

6. Penteriani, V., Gallardo, M., & Roche, P. 2002. Landscape structure and food supply affect eagle owl (Bubo bubo) density and breeding perfor

1. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (2016). www.cites.org. Available 7/2017.

2. Holt, D.W., Berkley, R., Deppe, C., Enriquez Rocha, P.L., Petersen, J.L., Rangel Salazar, J.L., Segars, K.P., & K.L. Wood. (1999). Family Strigidae (Typical Owls). Pp. 76-243 in: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1999). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barnowls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

3. International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2016). www.iucnredlist.org. Available 7/2017.

4. Martinez, J.A., Serrano, D., & Zuberogoitia, I. 2003. Predictive models of habitat preferences for the Eurasian eagle owl Bubo bubo: a multiscale approach. Ecography 26:21-28.

5. Penteriani, V., Delgado, M. M., Maggio, C., Aradis, A., & Sergio, F. 2004. Development of chicks and predispersal behavior of youn in the Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo). Ibis 147 (1):155-168.

6. Penteriani, V., Gallardo, M., & Roche, P. 2002. Landscape structure and food supply affect eagle owl (Bubo bubo) density and breeding perfor

|

Date of Last PVA/B&T Plan

12/2017 Current Population Size (N) 67.56.5 (128) Current Number of Participating AZA Member Institutions 56 Projected % GD at 100 years or 10 generations** 85.3% |

|

|

Population Analysis & Breeding and Transfer Plan

Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) AZA Species Survival Plan® Red Program |

Sustainability Report

Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo)

AZA Species Survival Plan® Yellow Program

Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo)

AZA Species Survival Plan® Yellow Program

Officers

|

Name

|

Organization

|

Position

|

|

Smithsonian National Zoological Park

|

SSP Program Leader & Studbook

|

|

Smithsonian National Zoological Park

|

SSP Vice Program Leader

|

|

Brandywine Zoo

|

Education Advisor

|