-

Natural History

-

SSP

-

Organizations

<

>

Also known as the Milky Eagle Owl or Giant Eagle Owl

|

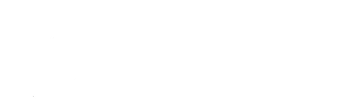

Taxonomy & Range

Verreaux’s Eagle Owl was originally described (as Strix lactea) by Temminck in 1820, based on a Senegalese type specimen. With no recognized subspecies, Verreaux’s Eagle Owl inhabits open thorny savanna, riparian woodland, savannahs and semi-desert within a patchy range that includes parts of central Africa as well as the majority of eastern and southern Africa. |

General Ecology

Weighing between 1.6 and 3.1 Kg, with a wingspan of up to 140 cm, Verreaux’s Eagle Owl is Africa’s largest owl species. Highly adaptable, Verreaux’s Eagle Owls tend to be crepuscular or nocturnal, hunting a huge variety of prey from the air or an open perch. Diet consists of mammals (including primates, mongooses, hyraxes, hedgehogs, small antelope, young pigs, fruit bats and rodents), birds up to the size of herons (Ardea), raptors or secretary birds (Sagittarius), reptiles, and even insects (which may be caught on the wing).

Weighing between 1.6 and 3.1 Kg, with a wingspan of up to 140 cm, Verreaux’s Eagle Owl is Africa’s largest owl species. Highly adaptable, Verreaux’s Eagle Owls tend to be crepuscular or nocturnal, hunting a huge variety of prey from the air or an open perch. Diet consists of mammals (including primates, mongooses, hyraxes, hedgehogs, small antelope, young pigs, fruit bats and rodents), birds up to the size of herons (Ardea), raptors or secretary birds (Sagittarius), reptiles, and even insects (which may be caught on the wing).

|

Breeding Biology

Breeding at the age of three to four years, these owls tend to be monogamous, using the same nesting site year after year; Verreaux’s Eagle Owls have been known to use nests built by other birds, nest in tree cavities, or on the ground. Two eggs are laid, with up to a seven-day laying interval, and incubated (almost exclusively by the female) for 32-39 days. White and fluffy at hatch, owlets develop quickly, fledging at 63 days. Cainism is common in this species, with older young preying upon younger owlets. Juveniles of this species have been known to remain with parents for up to two years, and have been observed assisting in the rearing of subsequent broods (a behavior unusual among owls). Parents can be very aggressive within their nesting territory, but like many owls, may also be very sensitive to disturbance, potentially abandoning eggs or young when disturbed. |

|

Present Status & Threats to Survival

The Verreaux’s Eagle Owl is not currently threatened with extinction (IUCN, 2014), with an estimated global range of over 11 million square kilometers. Eagle owls are, however, subject to relatively high levels of commercial pressure, and are coveted by hobbyists; they have been listed on CITES Appendix II since June 1979 (CITES, 2014). While the adaptability of this species has allowed them to make use of even altered habitats, human persecution remains among the most significant threats to their future well-being (Marcot, 2007; Virani & Watson, 1998). Negative superstitions about owls are pervasive throughout eastern and southern Africa; in one Malawi survey, 90% of respondents connected owls with bad luck, witchcraft and death (Enriquez & Mikkola, 1997). One in four respondents either had killed an owl or knew someone that had; reasons noted for killing an owl included “making magic medicine,” “because they make too much noise,” “to be eaten as a relish,” and “because it was nesting too near the house.” In follow-up surveys, few Malawi respondents had ever been exposed to owls in anything other than a negative context. Surveys in Costa Rica, where respondents were more familiar with owl biology as a result of visits to zoological parks, as well as greater access to television programming, indicated greater tolerance of the birds. Future educational initiatives may be crucial to this species’ long-term survival. |

Destruction of suitable habitat via agricultural conversion, and exposure to potentially harmful chemicals via pesticide applications continue to affect this species negatively (Keith & Bruggers, 1998). While Verreaux’s Eagle Owl is common in some parts of the range, global population trends have not been quantified, and the species remains vulnerable to a host of potential threats, due in part to their position at the apex of African savanna food chains.

|

Conservation Priorities

Conservation measures that have been undertaken include 1legal protection in many parts of the species’ range, 2international agreements to protect the species from commercial trade (i.e. CITES), and 3extensive research on the breeding habits and ecology of European populations. Despite protected status, the species is still persecuted in many parts of their range (Holt et al., 1999), pesticides may be particularly problematic to these apex predators, no detailed data on Asian populations exist, and efforts must be made to protect nesting territories (and potential territories) from additional development. Moving forward, lessons learned from Eurasian Eagle Owl conservation and reintroduction programs may be crucial to the success of efforts to conserve critically endangered relatives (including Blakiston’s eagle owl, Bubo blakistoni, among the world’s rarest owls).

Despite protected status, no detailed data on wild populations exist. As is the case with many large raptors, efforts must be made to protect nesting territories (and potential territories) from additional development.

Conservation measures that have been undertaken include 1legal protection in many parts of the species’ range, 2international agreements to protect the species from commercial trade (i.e. CITES), and 3extensive research on the breeding habits and ecology of European populations. Despite protected status, the species is still persecuted in many parts of their range (Holt et al., 1999), pesticides may be particularly problematic to these apex predators, no detailed data on Asian populations exist, and efforts must be made to protect nesting territories (and potential territories) from additional development. Moving forward, lessons learned from Eurasian Eagle Owl conservation and reintroduction programs may be crucial to the success of efforts to conserve critically endangered relatives (including Blakiston’s eagle owl, Bubo blakistoni, among the world’s rarest owls).

Despite protected status, no detailed data on wild populations exist. As is the case with many large raptors, efforts must be made to protect nesting territories (and potential territories) from additional development.

Notes on Verreaux’s Eagle Owls in Captivity

The first recorded appearance of Verreaux’s Eagle Owl in North American zoological collections occurred in September 1941, with the importation of 00.01.00 bird to the Bronx Zoo; the first successful North American captive hatch occurred at Riverbanks Zoo in April 1977.

This species has only been housed successfully in one mixed-species exhibit, in which 00.02.00 owls were housed with Palm-nut Vultures (Gypohierax angolensis). As of this studbook’s publication, aggression from nesting vultures had necessitated removal of the owls. Due to this species’ aggressive nature, they are not recommended for mixed-species exhibits; during nesting season, pairs may be particularly territorial, and protective gear may be required for animal care staff.

While the species was never historically housed in large numbers in North American collections, there is considerable interest in working with Verreaux’s Eagle Owls in the future. Potential additional founder stock has been identified in European and South African collections; the addition of new bloodlines to the North American population would be particularly beneficial.

The first recorded appearance of Verreaux’s Eagle Owl in North American zoological collections occurred in September 1941, with the importation of 00.01.00 bird to the Bronx Zoo; the first successful North American captive hatch occurred at Riverbanks Zoo in April 1977.

This species has only been housed successfully in one mixed-species exhibit, in which 00.02.00 owls were housed with Palm-nut Vultures (Gypohierax angolensis). As of this studbook’s publication, aggression from nesting vultures had necessitated removal of the owls. Due to this species’ aggressive nature, they are not recommended for mixed-species exhibits; during nesting season, pairs may be particularly territorial, and protective gear may be required for animal care staff.

While the species was never historically housed in large numbers in North American collections, there is considerable interest in working with Verreaux’s Eagle Owls in the future. Potential additional founder stock has been identified in European and South African collections; the addition of new bloodlines to the North American population would be particularly beneficial.

Sources Cited:

1. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (2014). www.cites.org. Available 07/2014.

2. Enriquez, P.L. & Mikkola, H. 1997. Comparative study of general public owl knowledge in Costa Rica, Central America, and Malawi, Africa. In: Duncan, J.R., Johnson, D. H., & Nicholls, T. H., eds. Biology and Conservation of Owls in the Northern Hemisphere. General Technical Report NC-190. St Paul, Minnesota: USDA Forest Service.

3. Holt, D.W., Berkley, R., Deppe, C., Enriquez Rocha, P.L., Petersen, J.L., Rangel Salazar, J.L., Segars, K.P., & K.L. Wood. (1999). Family Strigidae (Typical Owls). Pp. 76-243 in: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1999). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barnowls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

4. International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2014). www.iucnredlist.org. Available 07/2014.

5. Keith, J. O. & Bruggers, R. L. 1998. Review of hazards to raptors from pest control in Sahelian Africa. J Raptor Res 32(2):151-158.

6. Marcot, B. G. 2007. Owls in native culture of central Africa and North America. Tyto 11:5-9.

7. Virani, M. & Watson, R. T. 1998. Raptors in the East African tropics and Western Indian Ocean islands: state of ecological knowledge and conservation status. JK Raptor Res 32(1):28-39.

1. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (2014). www.cites.org. Available 07/2014.

2. Enriquez, P.L. & Mikkola, H. 1997. Comparative study of general public owl knowledge in Costa Rica, Central America, and Malawi, Africa. In: Duncan, J.R., Johnson, D. H., & Nicholls, T. H., eds. Biology and Conservation of Owls in the Northern Hemisphere. General Technical Report NC-190. St Paul, Minnesota: USDA Forest Service.

3. Holt, D.W., Berkley, R., Deppe, C., Enriquez Rocha, P.L., Petersen, J.L., Rangel Salazar, J.L., Segars, K.P., & K.L. Wood. (1999). Family Strigidae (Typical Owls). Pp. 76-243 in: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1999). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Barnowls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

4. International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2014). www.iucnredlist.org. Available 07/2014.

5. Keith, J. O. & Bruggers, R. L. 1998. Review of hazards to raptors from pest control in Sahelian Africa. J Raptor Res 32(2):151-158.

6. Marcot, B. G. 2007. Owls in native culture of central Africa and North America. Tyto 11:5-9.

7. Virani, M. & Watson, R. T. 1998. Raptors in the East African tropics and Western Indian Ocean islands: state of ecological knowledge and conservation status. JK Raptor Res 32(1):28-39.

|

Date of Last PVA/B&T Plan

8/2015 Current Population Size (N) 11.08.2 (21) Current Number of Participating AZA Member Institutions 10 Projected % GD at 100 years or 10 generations** 73% |

|

|

Population Analysis & Breeding and Transfer Plan

Verreaux's Eagle Owl (Bubo lacteus) AZA Species Survival Plan® Red Program |

Officers

|

Name

|

Organization

|

Position

|

|

Zoo Atlanta

|

SSP Program Leader & Studbook

|

|

Brandywine Zoo

|

Education Advisor

|