Photo: Kelly Bull, Windhoek, Namibia

-

Natural History

-

SSP

-

Organizations

-

Conservation Action

<

>

|

Introduction: The African pygmy falcon (Polihierax semitorquatus) is a small raptor found in northeast and southwest Africa. The species is one of the few bird species that are “obligate nest pirates”, primarily occupying the nests of social weavers and white-headed buffalo weavers. In captivity, African pygmy falcons are a popular education species.

|

Physical Characteristics

Adult birds weigh 4.2-7.2 kilograms and have an average wingspan of 2.2 meters, with females typically slightly larger than males. Adult plumage is brownish buff overall with blackish-brown flight feathers and tail, light wing linings, a light neck ruff and a patch of white feathers over the lower back that is not visible when the wings are folded. The bill is long and powerful. The coracoid patches are dark. The skin of the head is black and sparsely covered with pale down. The eye is dark brown and the feet and legs are blackish. Juveniles are darker overall and lack the light ruff color and white rump patch which begin to appear in the fourth year. Adult plumage is attained by six to seven years of age.

Adult birds weigh 4.2-7.2 kilograms and have an average wingspan of 2.2 meters, with females typically slightly larger than males. Adult plumage is brownish buff overall with blackish-brown flight feathers and tail, light wing linings, a light neck ruff and a patch of white feathers over the lower back that is not visible when the wings are folded. The bill is long and powerful. The coracoid patches are dark. The skin of the head is black and sparsely covered with pale down. The eye is dark brown and the feet and legs are blackish. Juveniles are darker overall and lack the light ruff color and white rump patch which begin to appear in the fourth year. Adult plumage is attained by six to seven years of age.

|

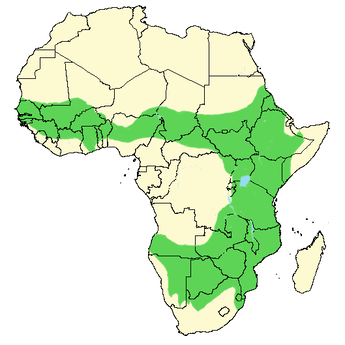

Taxonomy & Range

The species is found throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa. White backed vultures are found in most habitats, including savannah, open woodland, riparian and open swamp, but not in dense forest or desert. Feeding & Behavior

Carrion is the sole diet, with large carcasses preferred. These vultures spend much of their day soaring in search of carcasses, often following other scavengers such as hooded vultures, juvenile bataleurs and Rüppell’s vultures. Competition over food with conspecifics and other scavengers is vigorous, with fights common but injuries rare. |

White-backed vultures are highly gregarious, roosting and feeding in large groups. They are not migratory but must forage over large areas and may follow their food supply. Vultures rely on thermal updrafts of air in order to soar and glide, typically not becoming active until late morning when the air is warm enough to rise. Vocalizations are limited to a variety of chittering and squealing, with much cackling among birds at the carcass and hissing from dominant birds. Roosting is exclusively in large trees,

preferably those that are relatively bare to afford a view of the surrounding area.

preferably those that are relatively bare to afford a view of the surrounding area.

Breeding

The species breeds in loose colonies of five to twenty pairs and occasionally singly. Displays consist primarily of the pair circling together over the nesting area. A single white egg is laid in a relatively small, shallow nest of sticks, lined with grasses and leaves, built in the crown or a sturdy fork of the tree 5-50 meters above the ground. Incubation is done primarily by the female and lasts 56 days. The male provisions her during incubation and the early nestling period until the chick’s needs are such that both

parents must forage to meet them. Chicks fledge at 120-130 days but continue to remain dependent on the parents for several months until they are able to compete effectively at the carcass.

The species breeds in loose colonies of five to twenty pairs and occasionally singly. Displays consist primarily of the pair circling together over the nesting area. A single white egg is laid in a relatively small, shallow nest of sticks, lined with grasses and leaves, built in the crown or a sturdy fork of the tree 5-50 meters above the ground. Incubation is done primarily by the female and lasts 56 days. The male provisions her during incubation and the early nestling period until the chick’s needs are such that both

parents must forage to meet them. Chicks fledge at 120-130 days but continue to remain dependent on the parents for several months until they are able to compete effectively at the carcass.

Present Status & Conservation

Although the wild population is estimated at 270,000 birds, the white-backed vulture is now listed as endangered by IUCN due to the rapid decline in the population across its extensive range in central and southern Africa. Over an estimated 3 generations, or 55 years, the population has decreased by more than 50% overall and more than 90% in West Africa due to multiple serious threats.

In addition to habitat loss to farming and ranching and significant reductions in populations of large mammals on which the birds feed, vultures are increasingly subjected to poisoning, both unintentional from carcasses dosed by landowners to destroy mammal scavengers, and intentional from elephant and rhino carcasses laced with agricultural pesticides by poachers to avoid detection of their activities. In West Africa, the use of vulture parts for traditional medicine and cultural practices intended to bring good luck is widespread and has become commercialized. As with large birds all over the world, collision with power lines is a significant cause of mortality. An additional threat may be posed by the use of the drug Diclofenac, which is used in veterinary medicine to treat livestock but is highly toxic to vultures and has therefore resulted in the near-extinction of 3 species of vultures in India and neighboring countries.

Although the wild population is estimated at 270,000 birds, the white-backed vulture is now listed as endangered by IUCN due to the rapid decline in the population across its extensive range in central and southern Africa. Over an estimated 3 generations, or 55 years, the population has decreased by more than 50% overall and more than 90% in West Africa due to multiple serious threats.

In addition to habitat loss to farming and ranching and significant reductions in populations of large mammals on which the birds feed, vultures are increasingly subjected to poisoning, both unintentional from carcasses dosed by landowners to destroy mammal scavengers, and intentional from elephant and rhino carcasses laced with agricultural pesticides by poachers to avoid detection of their activities. In West Africa, the use of vulture parts for traditional medicine and cultural practices intended to bring good luck is widespread and has become commercialized. As with large birds all over the world, collision with power lines is a significant cause of mortality. An additional threat may be posed by the use of the drug Diclofenac, which is used in veterinary medicine to treat livestock but is highly toxic to vultures and has therefore resulted in the near-extinction of 3 species of vultures in India and neighboring countries.

Conservation Priorities

This species, along with 5 other African vulture species, are part of the African Vulture SAFE program.

This species, along with 5 other African vulture species, are part of the African Vulture SAFE program.

Sources Cited:

1. BirdLife International. 2008. Gyps africanus. In: IUCN 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. www.iucnredlist.org.

2. Brown, Leslie and Dean Amadon. Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World. 1989. Wellfleet Press. Secaucus, New York.

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. 2009. CITES Species Database. www.cites.org/eng/resources/species.html.

3. Del Hoyo, Josep, Andrew Elliott and Jordi Sargatal, eds. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. 1994. Lynx Edicions. Barcelona.

4. Ferguson-Lees, James and David A. Christie. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Miflin Company. Boston.

5. Mundy, Peter, Duncan Butchart, John Ledger and Steven Piper. The Vultures of Africa. 1992. Acorn Books. Randburg, South Africa.

6. Stattersfield, Alison J. and David R. Capper. 2000. Threatened Birds of the World. Bird Life International. Barcelona and Cambridge.

7. Wilbur, Sandford R. and Jerome A. Jackson, eds. 1983. Vulture Biology and Management. University of California Press. Berkeley.

1. BirdLife International. 2008. Gyps africanus. In: IUCN 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. www.iucnredlist.org.

2. Brown, Leslie and Dean Amadon. Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World. 1989. Wellfleet Press. Secaucus, New York.

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. 2009. CITES Species Database. www.cites.org/eng/resources/species.html.

3. Del Hoyo, Josep, Andrew Elliott and Jordi Sargatal, eds. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. 1994. Lynx Edicions. Barcelona.

4. Ferguson-Lees, James and David A. Christie. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Miflin Company. Boston.

5. Mundy, Peter, Duncan Butchart, John Ledger and Steven Piper. The Vultures of Africa. 1992. Acorn Books. Randburg, South Africa.

6. Stattersfield, Alison J. and David R. Capper. 2000. Threatened Birds of the World. Bird Life International. Barcelona and Cambridge.

7. Wilbur, Sandford R. and Jerome A. Jackson, eds. 1983. Vulture Biology and Management. University of California Press. Berkeley.

|

Date of Last PVA/B&T Plan

1/2017 Current Population Size (N) 11 birds (6 males, 5 females) Current Number of Participating AZA Member Institutions 4 Projected % GD at 100 years or 10 generations** 56.2% |

|

|

Population Analysis & Breeding and Transfer Plan

African White-backed Vulture (Gyps africanus) AZA Species Survival Plan® Red Program |

Sustainability Report

African White-backed Vulture (Gyps africanus)

AZA Species Survival Plan® Red Program

African White-backed Vulture (Gyps africanus)

AZA Species Survival Plan® Red Program

Officers

|

Name

|

Organization

|

Position

|

|

Dallas Zoo

|

SSP Program Leader

|

|

Los Angeles Zoo

|

SSP Studbook Keeper

|

|

Brandywine Zoo

|

Education Advisor

|

AZA SAFEThe African Vulture SAFE program is focusing on the conservation, restoration, and field research of the African White-Backed vulture.

|

VulProVulPro’s work in South Africa involves instrumental veterinary toxicological research, colony monitoring, and rehabilitation of injured vultures. Additionally, VulPro breeds nonreleasable Cape Vultures, African White-backed Vultures, Lappet-faced Vultures, and White-headed Vultures as part of a conservation breeding and reintroduction program where all offspring are returned to the wild. Public education is also a large aspect of VulPro’s work, both to school groups and local communities as well as visiting researchers looking to gain invaluable field experience in areas such as capturing, tagging, monitoring and rescuing vultures.

VulPro is one of the organizations supported by African Vulture SAFE. |

AZA SAFEThe African Vulture SAFE program is focusing on the conservation, restoration, and field research of the African White-Backed vulture.

|